Lymphoma in Dogs and Cats

— By Dr. Anna Adams, DVM —

Lymphoma is a highly malignant cancer that affects both humans and animals. It is one of the most common cancers in dogs and cats. In this article, we will provide an overview of this disease and answer questions that frequently arise.

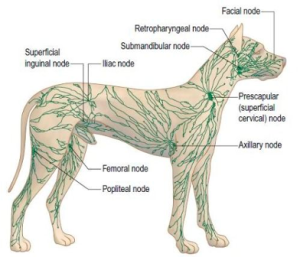

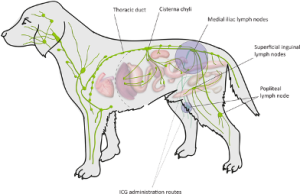

Lymph nodes are part of the body’s immune system. In healthy humans and animals, the lymph nodes are a hub for lymphocytes, which are a specific type of white blood cell. As our immune system needs them, lymphocytes divide and are deployed to specific areas of the body to fight infection. Lymph nodes are located in multiple areas across the body. Some lymph nodes are ‘peripheral’ and can be felt during a physical exam. Other lymph nodes are internal (in the chest, abdomen, or skull) and require machines (x-ray, ultrasound, CT, or MRI) to examine. Lymph nodes are interconnected by a network of lymphatic vessels. These serve as a pathway for lymphocytes and other white blood cells to move around the body, fighting infection.

What is Lymphoma?

What is Lymphoma?

Lymphoma arises when a normal lymph cell mutates into a cancerous one. This cell then divides uncontrollably and spreads to other areas of the body. Lymphoma will usually first arise in one single lymph node and then travel through lymph vessels to affect close-by nodes. These rogue lymphocytes will continue to spread to lymph nodes across the entire body.

Cancerous lymph cells do not just affect lymph nodes. They can also infiltrate any organ, causing organ damage and even failure. Some common organs that are affected are the spleen, liver, and intestines. In the latest stages of lymphoma, it will spread to the bone marrow, spinal cord, and brain.

Lymphoma is a highly malignant cancer, and without treatment, the average life expectancy is 4-8 weeks after the time of diagnosis.

What are Symptoms of Lymphoma in Dogs and Cats?

Lymphoma is common in both dogs and cats, but it tends to affect each species slightly differently. Both species are typically middle-aged to senior when diagnosed; however, lymphoma can also affect young animals.

The most common presentation for dogs with lymphoma is that one or more lumps have been felt. These ‘lumps’ are found to be enlarged lymph nodes. Many times, the dog has no other symptoms. However, other symptoms might include increased thirst/urination, malaise, decreased appetite, or fever.

In cats, the most common form of lymphoma is intestinal, affecting the GI tract. Common symptoms of this type of lymphoma include long-standing diarrhea, decreased appetite, weight loss, and vomiting.

Because lymphoma can affect any organ, there is a diverse array of presentations and symptoms that can be seen. The more atypical the symptoms, the more testing that will be needed for an accurate diagnosis.

How is Lymphoma Diagnosed?

Lymphoma is diagnosed by taking a sample of an enlarged lymph node or a sample of an affected organ and sending it to the laboratory for analysis. Sometimes this sample can be obtained using a thin needle and syringe. This is called FNA (fine needle aspiration) or cytology. Other times, we require a larger tissue sample which must be obtained surgically. This is called biopsy or histopathology. The samples needed vary with each case. Sometimes we require more than one sample to fully understand and classify the lymphoma. Your veterinarian will help to guide you through the sample collection process.

What is Staging?

What is Staging?

The extent of lymphoma can vary from only affecting one lymph node to affecting multiple organs throughout the body. The term ‘staging’ means classifying the extent of the cancer by determining which parts of the body are affected. The more areas affected, the higher the stage.

Generally, the stages of lymphoma are classified as:

- Single tumor or single lymph node affected

- More than one lymph node affected but only on one side of the diaphragm (either the front OR back half of the body, but not both)

- Multiple lymph nodes affected, spanning across the diaphragm (located in both the front AND back half of the body)

- Liver and/or spleen involvement

- Bone marrow and/or central nervous system involvement

*This is a generalized list. The staging can vary depending on species (dog vs. cat) and specific type of lymphoma.

To diagnose the stage of lymphoma, the veterinarian will need to perform additional tests including blood work and imaging (x-rays and ultrasound). Some animals require more advanced imaging such as CT or MRI and will need to be referred to specialty centers. These tests also help the veterinarian to determine whether the patient is healthy enough to undergo treatment.

What is the difference between remission and cure?

Remission means that there isn’t any evidence of cancer on physical exam, blood work, or imaging tests. However, it allows for the chance that some microscopic, undetectable cancer continues to exist in the body.

Cure is different than remission as it indicates that the patient is 100% free of cancer.

How is lymphoma treated?

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy conjures images of extreme nausea, pain, and weight/hair loss in humans. This is intimidating and off-putting for many pet owners who do not want to watch their beloved pets suffer. However, in most cases chemotherapy is a different experience for animals. The goal of chemotherapy in animals is remission and not cure. We therefore do not subject animals to intensive chemotherapy protocols, resulting in a less taxing experience.

Lymphoma is quite sensitive to chemotherapy, with roughly 75% of patients achieving remission. The length of remission varies depending on the chemotherapy protocol used and the stage/type of lymphoma being treated. The most common chemotherapy protocol is called CHOP. Variations of this protocol are commonly used as well. A chemotherapy treatment plan will be tailored to consider the patient’s coexisting conditions and lifestyle as well as the owner’s budget and schedule.

Steroid therapy

Steroids (e.g., prednisone) are a mainstay of treatment for lymphoma. Steroids are typically used in conjunction with chemotherapy although some pet owners elect to treat with steroids alone. Steroids will usually make patients feel better and improve their quality of life. Sometimes steroid treatment alone will result in short-term remission. However, steroid therapy on its own does not significantly change survival time compared to no treatment. Most animals treated with steroids alone will still only survive 4-8 weeks after diagnosis, but they will have the benefit of an improved quality of life during this time.

Supportive therapy

Management of gastrointestinal upset (vomiting, diarrhea, decreased appetite) is needed in many animals with cancer or who are undergoing cancer treatment. Anti-nausea medications (e.g. Cerenia), appetite stimulants (e.g., Entyce, mirtazapine), and/or antidiarrheal medications (e.g. metronidazole) may be needed.

What is the prognosis for animals with lymphoma?

The average life expectancy of an animal diagnosed with lymphoma who does not undergo any type of treatment is 4-8 weeks. The goal with full chemotherapy is to raise the expectancy to 6-12 months, but this is not guaranteed. This number is highly variable based on the species, stage, location, and type of lymphoma. Because this number is so highly variable, your veterinarian will be able to provide you with more accurate information regarding the prognosis of your individual pet.

Should I take my pet to an oncologist?

Veterinary oncologists are experts in the treatment and diagnosis of animal cancer. The option for a consultation with an oncologist should be considered for every lymphoma case. This is most important for complex and late-stage cases.

Chemotherapy and other lymphoma treatment may be pursued by general veterinarians with a special interest. Because lymphoma diagnosis and treatment is expensive, many pet owners will choose this as a less costly option. It should be understood that this does not come with the extensive expertise that a board certified oncologist can provide. However, this is a valid option if the finances or lifestyle do not allow for specialty referral.